Local police stockpile high-tech, combat-ready gear | America's War Within:

If terrorists ever target Fargo, N.D., the local police will be ready.

In recent years, they have bought bomb-detection robots, digital communications equipment and Kevlar helmets, like those used by soldiers in foreign wars. For local siege situations requiring real firepower, police there can use a new $256,643 armored truck, complete with a rotating turret. Until that day, however, the menacing truck is mostly used for training runs and appearances at the annual Fargo picnic, where it’s been displayed near a children’s bounce house.

“Most people are so fascinated by it, because nothing happens here,” said Carol Archbold, a Fargo resident and criminal justice professor at North Dakota State University. “There’s no terrorism here.”

Fargo, like thousands of other communities in every state, has been on a gear-buying spree with the aid of more than $34 billion in federal government grants since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on New York and the Pentagon.

The federal grant spending, awarded with little oversight from Washington, has fueled a rapid, broad transformation of police operations in Fargo and in departments across the country. More than ever before, police rely on quasi-military tactics and equipment, the Center for Investigative Reporting has found.

No one can say exactly what has been purchased in total across the country or how it’s being used,because the federal government doesn’t keep close track. State and local governments don’t maintain uniform records. But a review of records from 41 states obtained through open-government requests, and interviews with more than two-dozen current and former police officials and terrorism experts, shows police departments around the U.S. have transformed into small army-like forces.

Many police, including beat cops, now routinely carry assault rifles. Combined with body armor and other apparel, many officers look more and more like combat troops serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. The list of equipment bought with the federal grants reads like a defense contractor catalog. High-tech gear fills the garages, locker rooms and patrol cars in departments across the country.

Although local officials say they have become more cautious about spending in recent years, police departments around the country are continually expanding the equipment and tactics of their jobs, despite, in many cases, the lack of an apparent need.

The share of federal grants for Fargo and the county it anchors is more than $8 million, a considerable sum for terrorism defense given its remote location and status as one of the safest areas in America. Fargo has averaged fewer than two homicides a year since 2005, and there have been no prosecutions of international terrorism in the state for at least a decade, if ever.

North Dakota’s biggest city is a humble place set on plains so flat that locals like to say you can watch your dog run away for two weeks. Yet all patrol officers in Fargo now carry an assault rifle in their squad car.

Every community in the country has some explanation for why it needs more money, not less, to protect against every conceivable threat. It could be a shooting rampage at an amusement park, a weapon of mass destruction hidden at a manufacturing plant, a nuclear device detonated at a major coastal port. Nothing short of absolute security seems acceptable.

Law enforcement leaders nonetheless bristle at the word “militarization,” even if the defense community itself acknowledges a convergence of the two.

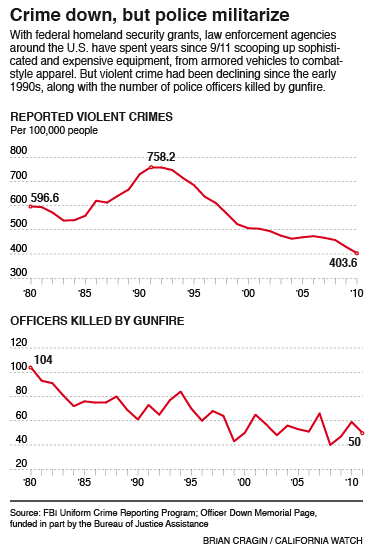

No one knows for sure the number of SWAT teams nationwide. But at a time when the crime rate has been dropping, the number of police associated with SWAT duties has gone up. The National Tactical Officers Association, which provides training and develops SWAT standards, has about 1,650 team memberships, up from 1,026 in 2000, according to Executive Director John Gnagey.

... a uniform message: The world is fraught with peril, and new high-tech gear is a solution.

Security analyst Dilip Sarangan of Frost & Sullivan, which tracks the homeland security industry, said security spending by governments and the private sector is “event-based.” Both are suddenly willing to budget more when tragedy ignites new anxieties, such as after the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, the 2005 London train bombings, the Mumbai terrorist attacks and, most of all, the 9/11 hijackings.

The homeland security market for state and local agencies is projected to reach $19.2 billion by 2014, up from $15.8 billion in fiscal 2009, according to the Homeland Security Research Corp.

New opportunities are making major defense corporations more a part of our domestic lives.

In 2007, British defense giant BAE Systems spent $4.5 billion to buy a company called Armor Holdings, which had subsidiaries that made and supplied police equipment, such as riot shields, hard-knuckle gloves, Delta 4 tactical helmets and laser sight mounts for AR-15 assault rifles.

Minnesota-based Alliant Techsystems, the Army’s primary provider of small-caliber ammunition, acquired in recent years two major tactical equipment suppliers, Blackhawk Industries and Eagle Industries. Company executives told shareholders that Blackhawk was a “highly profitable business,” with $115 million in predicted sales this year.

While such companies also outfit sporting enthusiasts and the military, law enforcement agencies are cast by Alliant as essential customers “in the rapidly growing security market.”

Local officials assert that homeland security grants, used to pay for the type of equipment showcased in Chicago, have slowed. But the grants still add up to a lot of spending: The Department of Homeland Security awarded more than $2 billion in grants this year, and President Barack Obama’s 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act pumped more than a half-billion dollars into existing grant programs.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is largely responsible for distributing homeland security grants. It operates a website known as the Responder Knowledge Base, which serves as a sort of war-on-terror catalog listing what local governments are allowed to buy with readiness funds.

Gnagey, of the tactical officers association, said there’s a sense among some local police that the price increases when makers know it’s being paid for with federal funds. The minute new equipment arrives, he joked, “if it’s painted black and called SWAT, the price doubles.”

But the evolution continues. In the Phoenix area, Sheriff Joe Arpaio claimed this year to have his own air armada of private pilots he could dispatch to monitor illegal border crossers. He called it Operation Desert Sky. Arpaio also picked up a full-size surplus Army tank, complete with treads.

The city of Ogden, Utah, is about to launch a 54-foot, remote-controlled “crime-fighting blimp” with a powerful surveillance camera affixed to its belly by the end of the year.

Standard-duty officers seen daily on the streets of Los Angeles were retrained to break in and kill terrorists without negotiating, under an assumption that the attackers could have a death wish and not be interested in resolving matters peacefully. Many officers were also equipped with assault rifles.

Las Vegas rushed forward as well. Everyday patrol officers were given additional training, and each shift now has “in-the-box” squads that can meet at a pre-determined location and respond as a group to would-be campus or casino attackers. Squad members carry additional gear in their cars, including gas masks, body armor and high-powered rifles.

Charles Ramsey, who was police chief in Washington, D.C., during 9/11, said officers in the nation’s capital began to train for multiple simultaneous attacks. The Mumbai bloodshed, which took place after Ramsey headed to Philadelphia in 2008, also served as a spur for him to make further changes and spend more money to up-armor his force.

Some 1,500 beat cops in Philadelphia have been trained to use AR-15 assault rifles – akin to the high-powered weapons issued to war fighters.

Fargo is not a place anyone associates with crime or terrorism. Its combination of friendly folk, low housing prices and high employment has garnered it recognition as one of the best places in the country to live. It is home to one of Microsoft's largest campuses and North Dakota State University.

Officials in Cass County, which includes Fargo, began buying gear in 2002. The spending on police gear rose from tens of thousands a decade ago to millions.

Police there said such spending is more than justified as a preventative measure. North Dakota has what could be perceived as targets, and the FBI established in Fargo one of its 104 Joint Terrorism Task Forces. Critical energy and agriculture sectors drive the booming economy in the remote border state. Drones used in the war on terror and homeland security are stationed at or operated from air bases in Grand Forks and at the local Fargo airport.

In addition, they say, some right-wing militias and white supremacists have been long-standing threats.

Other purchases, like the bomb-detection robots, are shared with federal agencies in Fargo that have outposts, but not the resources. The local police also say they’ve taken a regional approach to spend wisely, leveraging federal grants to buy equipment that has multiple uses.

This story was edited by Robert O’Harrow, Robert Salladay and Mark Katches. It was copy edited by Nikki Frick.

No comments:

Post a Comment